Wrestling With Demons:

In Search of the Real Ernest Hemingway

About Ernest M. Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) was an influential American novelist and short story writer, known for his distinctive style and portrayal of the "Lost Generation." Here's a brief bio of his life:

Early Life: Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, USA. He grew up in an upper middle-class family and developed an early interest in literature and outdoor activities. His hypomanic personality was a key factor influencing his writing.

World War I: Hemingway worked as an ambulance driver and canteen worker in Italy during World War I. This experience greatly influenced his writing, as he witnessed the brutality and disillusionment of war. The trauma he suffered was not so much from his wounds, but from the lies he told about his actions, injuries, and heroism in the trenches.

Paris Years: After the war, Hemingway first settled in Paris, where he became part of the expatriate community of writers and artists in the 1920s. He worked as a journalist and began his career as a fiction writer. After Paris, he lived in Key West, FL until 1939, when he moved to a little town just outside of Havana, Cuba.

Writing Style: Hemingway's writing style is characterized by simplicity, directness, and economy of language. He often employed a minimalist approach, using short sentences and a focus on dialogue to convey deep emotions and complex themes.

Major Works: Some of Hemingway's most famous works include:

"The Sun Also Rises" (1926)

"A Farewell to Arms" (1929)

"For Whom the Bell Tolls" (1940)

"The Old Man and the Sea" (1952), which won the Pulitzer Prize (1953) and contributed to the Nobel Prize in Literature (1954).

Personal Life: Hemingway had a tumultuous personal life, with four marriages and a reputation for a rugged, adventurous lifestyle. He was an avid traveler and enjoyed activities such as fishing and hunting.

Later Years: In the 1950s and early 1960s, Hemingway faced declining health and struggled with mental health issues. He tragically took his own life on July 2, 1961, in Ketchum, Idaho.

Legacy: Hemingway's impact on American literature is immense. He influenced a generation of writers with his distinct style and exploration of themes such as war, love, and the human condition. His works continue to be widely read and studied, and he remains a literary icon.

Hemingway's Demons

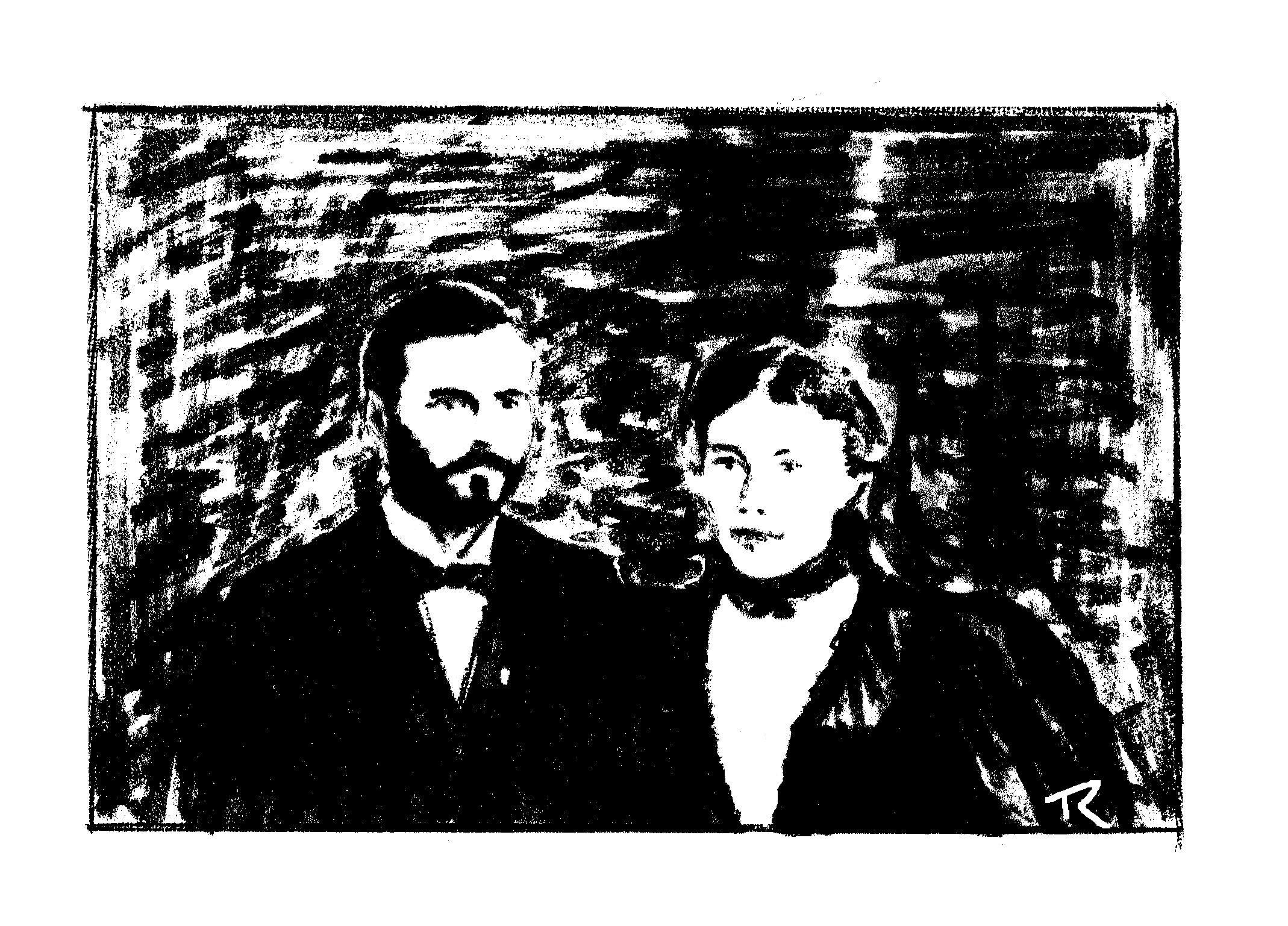

Parents: Ed & Grace

The quest for his parents’ approval haunted him. A strict, taciturn father and a flamboyant, narcissistic mother were a main source of angst.

Anguish: Depression, Alcoholism & More

A fourth demon is anguish, a result of depression, alcoholism, paranoia, homesickness for Cuba, and electroconvulsive shock treatments at the Mayo Clinic. His problems were worsened by the inherited personality trait known as hypomania, defined “as a mood state or energy level that is elevated above normal, but not so extreme as to cause impairment—the most important characteristic distinguishing it from mania.” Hemingway’s keen powers of observation, disciplined work ethic, and competitiveness were part of his hypomanic personality.

Rivalry: Lt. Edward M. McKey & Fedele Temperini

The fifth demon identified in the book addresses Hemingway’s unquenchable thirst to defeat those he saw as rivals, both dead and alive. Many historians focus on his rivalry with other writers. But this book contends that there were two non-writers who were perceived by Hemingway as rivals: Red Cross canteen worker, Edward M. McKey, and Italian infantryman, Fedele Temperini. Hemingway admired heroes, and he once said that in order to be a hero, one had to sacrifice his life. By this definition, McKey and Temperini both qualified. There is evidence to suggest that Hemingway was jealous of McKey’s “good fortune” to be the first real hero of the Piave; also, he was remorseful for causing “others” to die in war—he may well have been referring to Temperini.

Wives: Hadley, Pauline, Martha, & Mary

Hemingway was deeply remorseful for how he treated his wives, especially Hadley. It was she who enthusiastically encouraged him, bolstering his confidence that his writing was new and powerful. Also, it was she who originally came up with the iceberg theory to describe Hemingway’s writing style. Hemingway was haunted by their divorce, and he looked back with great remorse for his mistreatment of her. It was Pauline—wife number two—who ensured that he kept employing it. She carefully edited his work between 1926 and 1938, when he was most prolific. But Pauline’s wealth always bothered him; he needed her family’s money but he resented his dependence on her. Martha Gellhorn was a prolific writer in her own right, and she prompted her husband to begin writing again when he was happily resting on his laurels after the publication of For Whom the Bell Tolls in 1940. Hemingway loathed the competition. As for his last wife, Mary, she and Ernest constantly bickered. But, like his other wives, Mary read his work. From 1946 until his death in 1961, she played a role in his writing. A significant example of Mary’s influence was her plea that Hemingway refrain from killing off Santiago at the end of The Old Man and the Sea.

Pain: Injuries & Illnesses

A third demon is pain, starting with his mortar wounds in WWI. Most biographers have it right in one respect—Ernest Hemingway’s war experience in 1918 was a large factor influencing his future career as a writer. These writers surmise that a head concussion, leg wounds, and emotional trauma from an exploding shrapnel bomb supplied the impetus for so many of his future novels and short stories. Many scholars opine that he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This book offers a countervailing theory of this so-called “wound theory.”